One hundred years ago today, in early September, 1921, “Hurricane 2”, the 2nd named hurricane of the season, roared ashore in Mexico, just north of Tampico, packing 95 mph winds. It passed over the Rio Grande Valley, but lost a lot of wind power in the meantime. However, it headed straight to the San Antonio area with severe thunderstorms, where it dropped the heaviest rain seen in the region for over 6 years. San Antonio had recorded serious flood events over the years….1819, 1845, 1865, 1868, 1903, 1913 (October and December), and 1914, but the worst was about to occur.

In December 1920, the Boston-based engineering company Metcalfe and Eddy, supplied a “Report to the City of San Antonio,” which warned that a similar disaster to that of the 100 year flood of 1819 “is just as likely to occur next year as at any other time.”

The report was taken seriously, and decisions were made to protect San Antonio from future such events.

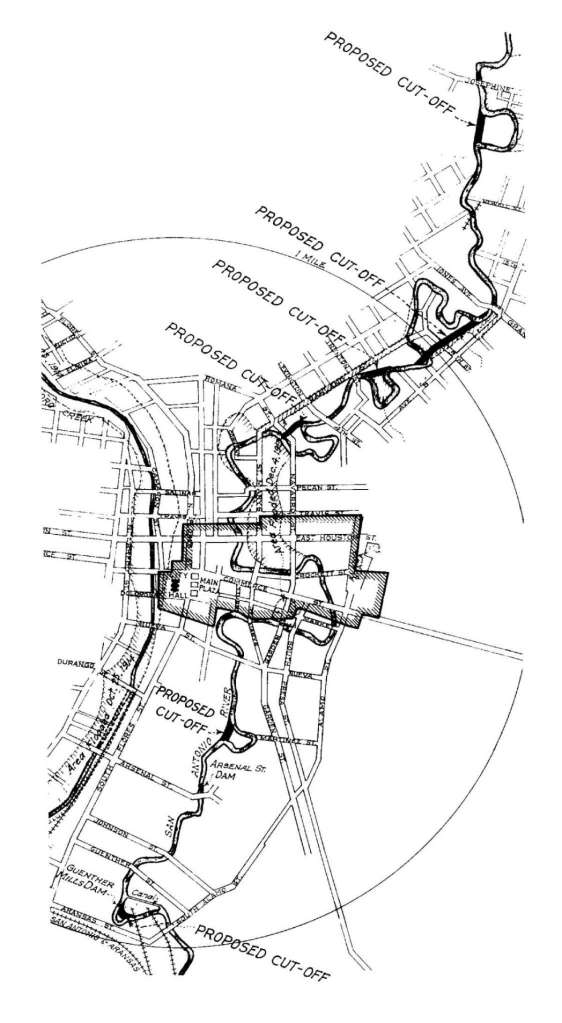

The proposed plan was the “straighten” the river by eliminating half a dozen bends, four of them north of the city, with two others on the southern course. This action would assist with the flow of the water, especially during flood events. This would cutoff over a mile of the length of the river.

One of the twisting bends was almost 1,500 feet of winding river north of Navarro Street that would be straightened to allow the construction of the Municipal Auditorium…now the site of the Tobin Center.

Photo: “A Report to the City of San Antonio” –Metcalfe & Eddy 1920 ( Courtesy “American Venice” Lewis Fisher )

Nine months after this plan was accepted, “Hurricane 2” hit the Mexican coastline.

The first showers arrived in San Antonio during the evening of Thursday September 8th, 1921, but by 6pm the next night, the area was being deluged by violent thunderstorms with torrential rain during the slow-moving depression.

Three hours later, the rain had eased, and locals retired for the evening thinking that the worst was over. However, as recordings show, the rainfall over the Olmos Creek north of the city, had been almost twice the volume that had fallen on the city.

By 9pm on the Fiday night, the creek began to break its banks. The San Antonio River swelled and was now rising one foot every five minutes. It swept through Brackenridge Park and sent campers racing for higher ground.

Three hours later at around midnight, the floodwaters broke the bank at St Mary’s Street, and within minutes, the swirling water was six feet deep through the streets of the city. At the historic Gunter Hotel on the corner of St. Mary’s and Houston, the water was cresting the mezzanine level of the building. Soldiers from surrounding army camps were quickly recruited to assist with the emergency. There were countless acts of heroism from members of the military and civilians who braved the swirling waters to rescue stranded people and bring them to safety.

Soon after the city was inundated, the water supply was shut off at the waterworks on Market Street, and within minutes, the water was overflowing the walls around the power plant on Villita Street ( the site of the current circular Villita Assembly Building ), and consequently the city’s electricity supply was cut off.

Oil from pump houses was swept up in the torrent, leaving high-water marks on buildings. The river was littered with debris such as furniture, pianos, lumber, vehicles, dead animals, even partial buildings, and when this all became trapped under bridges, the water was sent surging even higher into the city.

Sadly, in this darkness, people were caught up in the floodwaters, and desperate cries for help were heard throughout the night along the river. To the west of the city, the Alazan, Apache, San Pedro and Martinez Creek tributaries overflowed rapidly, and carried away the wattle and daub shacks and shanties built along the banks. When the river crested at around 2:30 am, it was estimated that over 7” of rain had fallen on San Antonio….with double that amount over the Olmos Creek area north of the city.

The morning light showed total devastation throughout the drenched city. Fourteen of the twenty-seven bridges downtown were destroyed. City streets were strewn with debris, roads were torn up, and streetcar rail lines were left twisted along the former sidewalks. The military was called in to assist with combating looters who were scouring stores to retrieve whatever they could from the sodden mess in water-logged buildings.

Photo: St Mary’s Street. Note the high water mark on the building ( Courtesy UTSA Libraries Special Collections )

Photo: Courtesy http://www.thealamocity.com

Photo: Sth St. Mary’s Street bridge. The International Center is currently located on the other side of the bridge, and today Homewood Suites is on the right of the photo ( Courtesy wwwthealamocity.com )

Photo: Soldiers maintaining order on the corner of N. St. Mary’s and E. Travis following the flood. On the left is the former Hotel Lanier and the “Cloonan & Osborn” Paint Store ( now parking garages ) Down the street, on the right in the distance, is the St Anthony Hotel. ( Courtesy San Antonio River Authority )

Photo: Commerce Street bridge near Losoya Street. Clifford Building on the right, current location of Schilo’s restaurant on the right hand side on the other side of bridge. The gap in the middle of the photo is now filled by the Hilton Palacio del Rio Hotel. ( Courtesy http://www.thealamocity.com )

The official death toll was 51 locally, with an additional 23 people missing. However, there are scholars who believe that the true numbers were considerably more than these official figures. The total damage was estimated to be $ 5 million, over $ 75 million dollars today. Meanwhile, across south-central Texas 224 people lost their lives in the tragedy, with damage exceeding $ 10 million (over $ 150 million dollars today).

Following this tragic event, the Olmos Dam was constructed in order to protect the city. Nineteen hundred feet wide, sixty feet high, and with a cost of $ 1.6 million, it was completed at the end of 1926. The dam spurred a building “boom” in the city center, and many of today’s iconic downtown buildings became a reality.

There was talk to fill in the Great Bend of the river, and pave it over to eliminate any future flooding of the city. Thanks to the efforts of the San Antonio Conservation Society and the City Federation of Women’s Club, a battle was launched to save the River Bend. Then in June of 1929, local architect Robert H. H. Hugman presented his plan for the San Antonio River, which was accepted by the city and became most of what we see along the Riverwalk today.

Later, floodgates were installed, a cutoff channel created, and huge tunnels dug under the city, which were all constructed to work together to prepare the city for any future catastrophic weather events.

* * *

Additional story:

Prior to the 1921 flood, the bridge spanning the San Antonio River at North St. Mary’s Street was referred to as the “Letters of Gold” bridge. It was a feature of the city. At the top of the bridge, there was a gold-colored plaque with inscription and gold ornamentation at each end of the bridge. The plaque above the span featured the name of the bridge builder (Berlin Iron Bridge Company — East Berlin Connecticut), the engineer of the city ( Paul Pretzer ), the name of the Mayor ( Bryan Callaghan ) and the date of construction ( 1890 )

Mayor Bryan Callaghan’s decision to include his name on the plaque was quite controversial….in fact, when he ran for re-election, the nomination was known as “The Letters of Gold Campaign “ Incidentally, he served a total of 9 terms as the city Mayor.

Following the flood, the “Letters of Gold” bridge was dismantled, and now is located at Brackenridge Park.

Photos: Author

Sources:

San Antonio Current: September 13, 2011 (Char Miller)

“River Walk…The Epic Story of San Antonio’s River” Lewis Fisher

San Antonio Public Library : mysapl.org/events

San Antonio: The Story of an Enchanted City Frank W Jennings

Follow My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.