Photo: San Antonio Report

Robert Harvey Harold Hugman was born the 3rd of three children to Robert Charles Harold Hugman and his wife Annie, and the family lived on a 7 acre property on Westfall Avenue in Denver Heights. At their home, the family had horses, cows, hogs, chickens, turkeys and guinea hens. On the land was a large orchard, and they also bred Cocker Spaniel dogs. The three Hugman childen were also permitted to keep a wide variety of pets including white mice, guinea pigs, rabbits, goats, and donkeys.

Early in 1919, the family sold the Westfall Ave property and bought a Queen Anne style home in the King William area for $3,700; however, here they were not able to keep the array of animals that they had enjoyed at their previous residence.

Photo: Hugman childhood house…..Author

In February 1920, the then 18 year old Robert Hugman graduated from Brackenridge High School. At school, he enjoyed participating in theatrical productions, and was an accomplished musician as well.

Photo: San Antonio Evening News

At the school, he was also an art student of Emily Edwards, who is known as the co-founder and first president of the Conservation Society. He had developed a passion for architecture, and he subsequently enrolled at the School of Architecture and Design at the University of Texas Austin. Shortly after his college graduation in 1924, Robert Hugman married Martha Aurora Smith, and the couple moved to New Orleans where Hugman worked as a draftsman.

Three years later in 1927, Robert Hugman and his young family returned to San Antonio. They rented a small 2 bedroom craftsman-style home in the King William district, and he established his own architect business in town. Coincidentally, at that time, there were discussions about flood prevention, and what to do to protect the city following the devastating flood of 1921. The city council had already decided to construct a large bypass channel to divert floodwaters from the Great Bend, and Robert Hugman envisioned how the meandering river through downtown San Antonio could become a place of beauty and charm in an urban linear park concept.

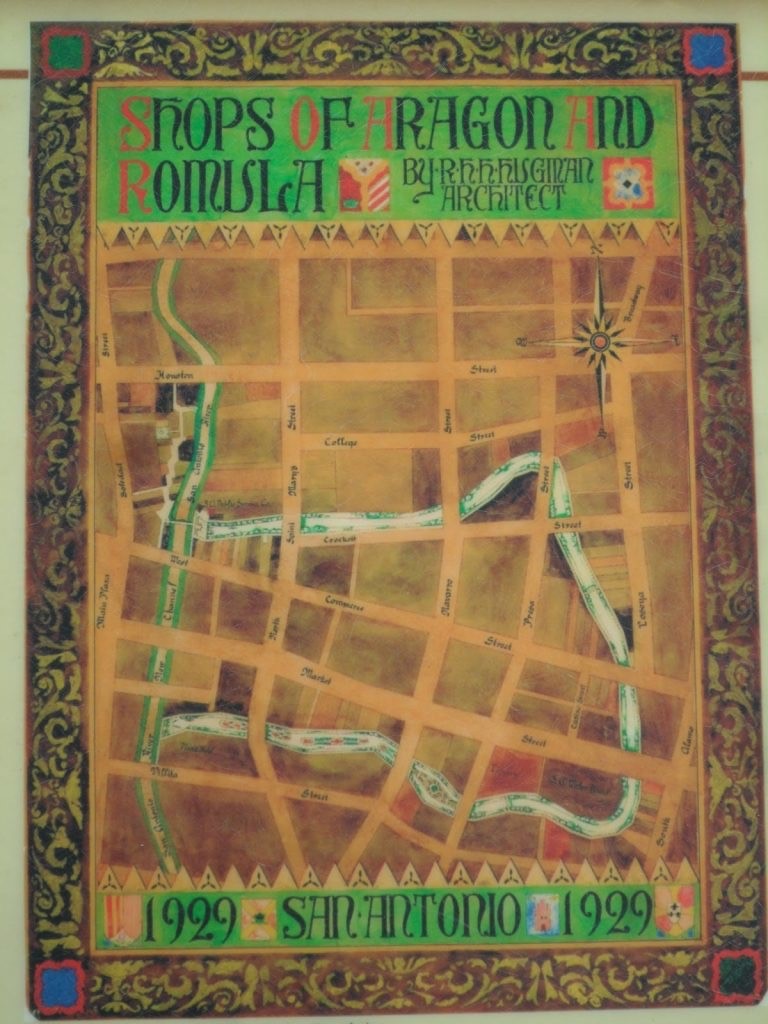

His plan was called The Shops of Aragon and Romula, and he drew inspiration from San Antonio’s Spanish heritage, combined with his memories of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre district.

Photo: WordPress

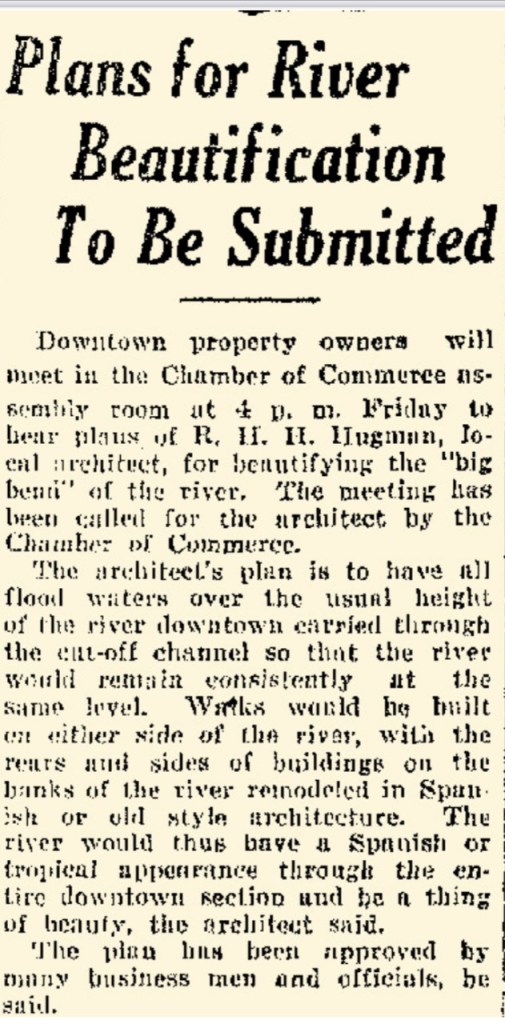

On Friday June 28, 1929, Robert Hugman was given the opportunity to present his ambitious plan for the Riverwalk to a meeting of city leaders, including the Mayor Charles McClellan Chambers, two city commissioners, civic leaders and property owners.

Photo: San Antonio Light

Photo: San Antonio Express News

Up to this time, there had been discussion to do away with the Great Bend, pave it over and incorporate it into a vehicular traffic way; however, there were groups, including the Conservation Society, who saw merit in utilizing the natural river. Also, sadly the Great Bend had become neglected, leading to littering, unsanitary water, and it was even perceived as a dangerous place to be.

Robert Hugman presented a well-researched and informative vision for the river, and said, “the historic tradition and natural beauty of the river must be sacredly preserved if we would build the right foundation for steady growth and future interest” that would transport visitors to another place.

At the meeting he first outlined the plan that he called “The Shops of Aragon.” This involved a small cobblestone street along the riverbank, behind businesses fronting Soledad, Houston, St. Mary’s and Commerce Streets. Here, there would be cafes, small shops, apartments, and dance clubs.

He also endorsed the construction of a heavy floodgate where the river turned to the east, at the northern end of the Great Bend.

A small stone footbridge near Commerce Street would allow pedestrian traffic from The Shops of Aragon, which would be outside the Great Bend into Romula which would have been inside the Great Bend. As it turned out, this footbridge was never constructed.

He saw this part of the river as an inviting stroll along a flagstone sidewalk, with shops and restaurants being developed on both sides of the river between Crockett and Commerce Streets. This area today is known as “River Square,” although Robert Hugman’s original name for this section of the riverwalk was the “Foods of all Nations”

Another part of his vision was to incorporate river craft that were modeled on the gondolas, similar to the ones that plied the canals of Venice, complete with gondoliers pushing the boats along the river using long poles.

In his presentation he said, “To me, the river is one of nature’s greatest gifts to San Antonio and should be appreciated and developed as such.”

Despite some support for his plan, even from Mayor Chambers, Hugman’s concept for the Riverwalk was passed over in favor of another proposal from a city planner from St. Louis, Harland Bartholomew.

Robert Hugman, although dejected, threw himself into other projects, and during the Depression, he worked as a planner with the Works Progress Administration (WPA), where he worked with District Director Edwin P. Arneson. Hugman helped reconstruct Woodlawn Lake and Seguin’s Starke Parke, he worked on Landa Park in New Braunfels and on Concepcion Park. Eventually, his designs came to the attention of Jack White, the manager of the upmarket Plaza Hotel on the river, and a future Mayor of San Antonio who was concerned about the “dirty little river” flowing past his hotel.

White met with Robert Hugman, Edwin Arneson and Henry Drought, who was the State Administrator of the WPA, and together, under White’s guidance, they formulated a plan for the WPA to carry out the Riverwalk restoration project, with funding assistance from Congressman Maury Maverick. No longer referred to as “Aragon and Romula,” Robert Hugman became the WPA’s architect for the enterprise in 1938.

The plan was altered with the Riverwalk project beginning further north at Lexington Avenue, and incorporating the natural river to the Great Bend, eliminating the lane from Houston Street, in favor of multiple, unique staircases from above to the river’s edge. The channel walls were converted to include irregular limestone blocks to give a more natural appearance.

The majority of the work concentrated on the Great Bend, with Robert Hugman’s artistic influence, and today as a result, visitors to the world-famous Riverwalk still witness his unique designs to beautify the waterway.

In a publicity event on the morning of March 29th, 1939, with approximately 300 residents as witness, Jack White using a “golden shovel”, officially broke ground on the Riverwalk beautification project at the Market Street bridge near the present site of the Casa Rio.

Photo: American Venice….Lewis Fisher

As one strolls along the river’s edge, Robert Hugman’s innovations are apparent, including the original floodgate at the northern entrance, a floating walkway, twisted brick columns, cedar benches, two beautiful arched stone bridges, several surprising designs including artificial stepping stones outside the La Mansion Hotel, water features and fountains incorporating air-conditioning runoff, long benches for opportunities to relax and take in the river’s ambiance, the outdoor river theater, named in honor of Edwin Arneson who passed away during the riverwalk restoration, and 31 distinctive staircases. Most of Hugman’s designs are represented by the small emblem alongside that bears his name.

Photo: Floodgate #3… Author

Photo: Hugman Floating Walkway…Author

Photo: Hugman Twisted Column…Author

Photo: Hugman cedar bench…Author

Photo: Hugman / Selena Bridge… Author

Photo: Rosita’s bridge and Arneson River Theater….Author

Photo: Hugman stepping stones and fountain….Author

Photo: Hugman bench…Author

Photo: Hugman water feature…Author

Photo: Hugman emblem….Author

During this time, there were many national articles written for publications applauding the work, and referring to the Riverwalk as “Venice of America” and “American Venice”

Despite the rejuvenation of San Antonio’s best asset, there were rumblings of discontent. Many civic leaders, conservationists, and other notable voices in the city, including renowned architect Atlee B. Ayers, were openly expressing their opposition to the river’s seemingly harsh appearance with the bright limestone walls, and lack of vegetation. Some even claimed the project was “a source of ridicule” for the city. Robert Hugman however, remained adamant that with the replacement of trees and the eventual growth of the vegetation, the banks would be more appealing with a softer feel. He actually had a documented plan to remove, cultivate and restore much of the vegetation along the banks. In fact, in his plan, there were 11,000 trees and plants located along the riverwalk.

Also, around this time, the Mayor, Maury Maverick, who was sponsoring a National Youth Administration Project to develop the La Villita area, and according to Hugman, Mayor Maverick,”became rather zealous to take over the river project” and tried to have Robert Hugman employ a landscape architect, who was part of the Maverick family. And to make matters worse, the Mayor wanted Hugman to contribute $35 a day out of his salary to pay the relative. When Hugman refused, the criticism of the restoration work began.

In March 1940, Hugman learned that a shipment of limestone had been reportedly diverted to the La Villita restoration project by Mayor Maury Maverick, and to Hugman’s dismay, upon filing a formal complaint to the riverwalk oversight committee about this apparent discrepancy, Robert Hugman was unceremoniously dumped from the Riverwalk project without even a hearing to present his concerns. In the committee’s words, they were “tired of the controversies.” In a later interview, Robert Hugman said, “It was the greatest disappointment of my life.”

At this time, he was living in a home near Brackenridge Park, and sadly here, he lost his first wife Martha. Following this tragedy, he moved his children, Robert Jr and Ann back to the King William area to live with his mother and sister.

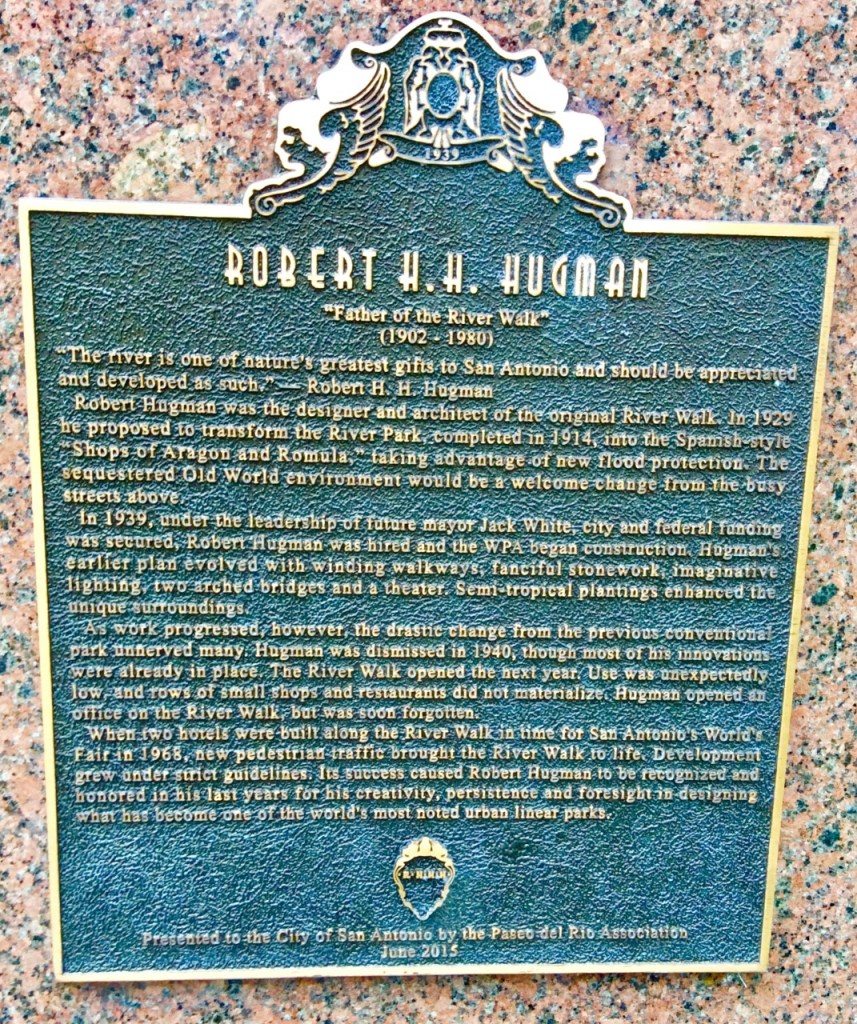

Robert Hugman was determined to show that his vision and plan would work for the Riverwalk, and apart from supporting the work as it continued, he established his architect’s office at river level in the Clifford Building next to the Commerce Street Bridge. Today, outside the building, there are plaques and a bronze bust of Robert Hugman, designed by Sean Klinksiek, whose great-uncle worked on the riverwalk restoration program.

Photo: Robert Hugman office and bust….Author

Photo: Plaque on Robert Hugman bust

Hugman operated his architect business by the river until 1957, at which time he was hired to work on several projects at Randolph Air Force Base, including the planning of flight simulators. He eventually retired in 1972.

Robert Hugman had established a friendship with Robert Turk, who was hired as the Superintendent of Construction. Their friendship deepened because of their daily walks along the river during the project, and the shared ideas for the completed work. Turk later said of Hugman, “ He was way ahead of his time. Most people didn’t understand what he was trying to do. I guess none of us realized the potential of the Riverwalk. He never really got over being fired. We would fish together after we both retired, and he talked about it many times. He felt somewhat better when he was honored at the Arneson River Theater in 1978, and efforts were made to recognize his original work.”

Photo: Hugman ceremony Arneson River Theater….San Antonio Express News

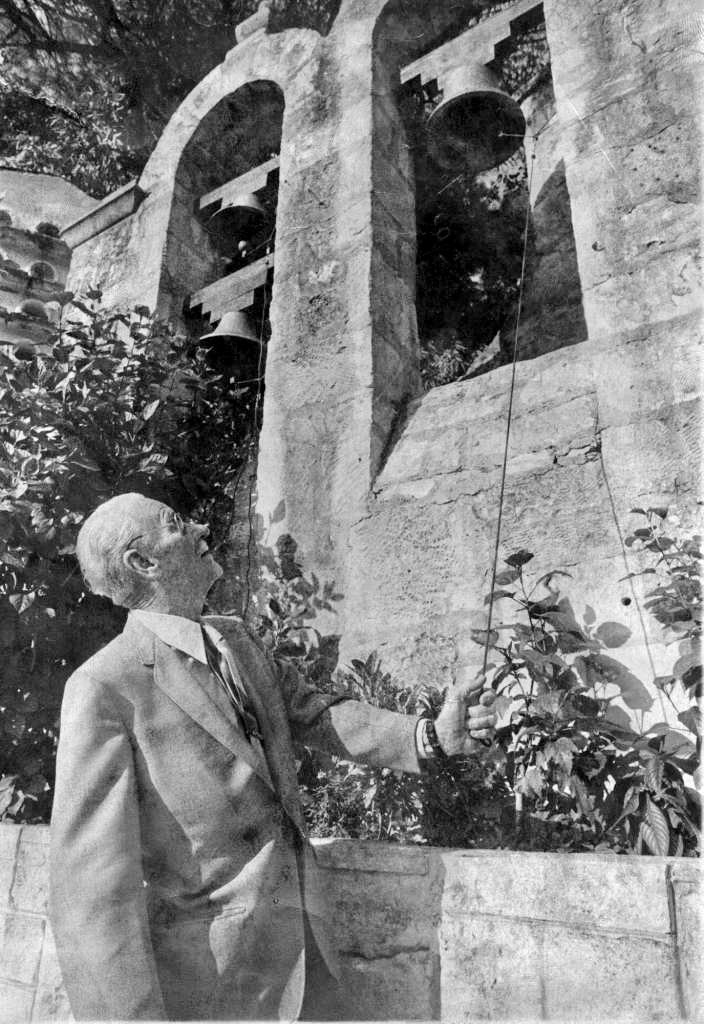

As Robert Turk mentioned, on November 1st, 1978, Robert Hugman was officially honored at a ceremony on the stage of the Arneson River Theater. This recognition was instigated by restaurant-owner Frank Phelps and his wife, who had discovered Hugman’s original plans for the Riverwalk, including bells behind the stage at the Arneson River Theater. Phelps contacted Carlos Garza, the only licensed bell-maker in Texas to discuss the plan, and within a few months, five bells were cast to fill the arches behind the stage, as Robert Hugman had envisioned. The largest bell weighed 125 pounds, and carries the inscription “In honor of Robert H. H. Hugman, concept architect, San Antonio River”

At the ceremony, Robert Hugman was honored and applauded for his vision. He gave a speech about how the idea was formulated, and then he, with Mayor Lila Cockrell by his side, ceremoniously rang the largest bell behind the stage, that bore his name.

Photo: Robert Hugman ringing his bell…Texas State Historical Association

The San Antonio Riverwalk not only showed what could be done with a natural park, but also showed other cities how to take advantage of their natural gifts.

Robert H. H. Hugman, “The Father of the Riverwalk” will always be remembered as a visionary, and a man ahead of his time.

The next time you are down by the Riverwalk, think of Robert Hugman, and maybe raise a glass in his honor for the gift that he gave to San Antonio.

Robert Hugman passed away in San Antonio on July 22nd, 1980 at the age of 78.

Photo: Robert Hugman headstone…Author

Additional stories:

- When Robert Hugman had devised his initial plan of “The Shops of Aragon and Romula,” there was some skepticism about the water-level shops. So he prepared a brochure and personally visited with prominent businessmen around the city to present it, and gain support for his idea. He ended up with 85 signatures from these citizens, and another 20 from other influential people including women’s groups, and the sculptor Gutzon Borglum who was living in San Antonio, and is remembered for many great artworks, including Mt Rushmore.

Photo: Gutzon Borglum working on a Mt Rushmore model…..reddit.com

- One of the features of Robert Hugman’s plan was the Arneson River Theater. According to Hugman in a later interview, this corner of the river was a notorious dumping ground of material from machine shops in that area. To build the theater, workmen had to remove old engines, machine parts and even old car bodies from the area where the theater’s seating is now.

Photo: Arneson Theater under construction……….Texas State Historical Association

Sources:

The writings of Marguerite E. Hugman 1970…….familysearch.org

KWA Newsletter August 2015

tshaonline.org

digital.utsa.edu

“A Dream Come True…Robert Hugman and San Antonio’s River Walk” Vernon G. Zunker

Speech by Robert Hugman at the Bexar County Historical Commission April 19, 1975

Interview by Doris Dupre with Robert Hugman at his home February 17, 1977.

“American Venice” Lewis Fisher

Follow My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.